Fat – a dirty word

Fat – A Dirty Word?

There are people you meet who have a profound impact on your life —Michael Levine is one of them. Recognized as an ‘eating disorders prevention expert’ he is much more. He is a ‘voice’, a window into the souls of women and girls through his sensitive articulation of the many issues that construct who we are. He is a conscience for men and boys, making this article an essential read for everyone.

Not only do his views have the potential for creating a better world but so too the experience of feeling his warmth; his depth of compassion and empathy; and most of all, his humility. The following article was written by Michael Levine for the Bronte Foundation newsletter ’Our Journey’ and Michael has kindly made it available to share on ‘Black Dog’. The article is presented in its entirety.

Article…

1 An attitudinal shift from body weight, dieting, and external regulation to health and health promotion will likely serve us well in preventing eating disorders and obesity.

By Micheal Levine

Throughout the world—Australia, Spain, Italy, Argentina, the United Kingdom, Canada, and the United States—an increasing number of professionals, nonprofit organizations, and citizens of all ages are committed to the prevention of eating disorders and related problems.

As readers of this newsletter know all too well, for various political, social, and economic reasons, far too many people suffering from eating disorders are unable to obtain effective treatment. And even if they could, there will never be enough treatment providers, let alone skilled and sensitive specialists, to help all the people with anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa, and so-called “subthreshold” problems.

Moreover, I believe that the attitudes and practices that will help prevent new eating disorders will also be of benefit to people in recovery and to their families.

This article, the first of a two-part series, discusses what I feel strongly are some important attitudes (beliefs, feelings, perspectives) for prevention. The next installment will consider what citizens can do in their personal and professional lives to prevent eating disorders and disordered eating. Much of the material in both parts is drawn from my talk at The Bronte Foundation conference in Melbourne in mid- March 2005, and from my recently published book on prevention (Levine & Smolak, 2005).

To “prevent” a disorder means to take specific actions to increase the probability that this disorder will not develop at all. Prevention not only supports current states of health and of effective functioning, it also promotes even greater well-being for people in general so that their resilience to potentially debilitating stressors will be enhanced (Albee, 1996). Prevention has two proactive goals. The proximal goal of prevention is to reduce the risk factors for a disorder and to increase sources of resilience. The distal goal is to avoid—or to delay for as long as possible—the onset of the disorder.

In their more charitable moments, critics of prevention tell us “Come on, really — You’re dreaming if you think you can change all the negative factors that contribute to eating disorders—sexism, mass media, mass marketing of instant gratification, weight-and-shape-related teasing, and so on.” I reply: “All right, but don’t revolutionary changes often begin with big dreams?” And “Wasn’t it a ‘Just a Big Dream’ in, say, 1950, to envision that a woman could and would be prime minister of England or a justice of the United States’ Supreme Court? So let’s dream for a while as we consider some attitudes concerning prevention that you and I can embrace in our everyday lives.

1. Eating disorders are about us and the worlds we construct. There are a number of epidemiological, research, and treatment-related advantages in thinking of anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa, and other eating disorders as severe, isolating illnesses with clear connections to genetics, biochemistry, stress-related hormones, and temperament. However, it is equally important that we constantly remind ourselves that people suffering from eating disorders and eating problems are, like those committed to prevention, people, not “anorexics” or “bulimics.”

In the development of their disorders and throughout recovery, they are people struggling with desires, fantasies, anxieties, developmental challenges, coping mechanisms—and, yes, dreams–established and vigorously reinforced by our culture (Gordon, 2000). At a basic level it is people, people like ourselves, who face life’s challenges and who suffer from eating disorders, depression, obsessions, and anxiety.

Thus, at a basic level eating disorders and eating problems are existential problems. They express (embody) issues (e.g., the meaning of femininity, of power, of good and evil) and processes (e.g., the construction of body image, one’s place in a family and in society, or engagement with mass media) that are embedded in the culture(s) we all live in and create (Gordon, 2000; Silverstein & Perlick, 1995; Thompson, Heinberg, Altabe, & Tantleff-Dunn, 1999).

This perspective has three important implications. First, prevention needs to acknowledge the context as much, if not more so, than individuals (Cowen, 1983). In thinking about the prevention of eating disorders and eating problems, the real challenge is Aus@ and the cultural contexts that we create, not the “anorexics” and “bulimics” (or “them”), no matter how alien or out-of control their behavior seems to us. Second, it is likely that prevention will fail–and may well be harmful–if we ignore widespread cultural attitudes and practices in order to concentrate solely on the definition of clinical syndromes, the portrayal of fascinating “cases,” and the dangers of extremely disordered eating.

According to this contextual or “ecological” perspective, prevention needs to emphasize the cost to individuals and to society of a set of issues, each of which can be conceptualized on a continuum of severity. These issues include, for example, negative beliefs and feelings about one’s body, a fear of fat, the internalization of impossible ideals of beauty, and unhealthy patterns of eating and of trying to manage one’s weight.

Third, it is serves little purpose to talk about whose fault an eating disorder is. Yet, it is absolutely imperative that we all take responsibility for creating healthier contexts for boys and girls and for ourselves.

2. Prevention, like treatment, is not “just a female issue” – Prevention is a community issue involving boys and men. The continuum of disordered eating, ranging from negative body image and unhealthy eating and weight management practices at one end to full-blown, life-threatening, and chronic eating disorders at the other end, constitutes an important issue not just for females, but for boys and men as well.

This is true in three important ways. First, although anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa are exceedingly rare in the general population of males (Hoek & van Hoeken, 2003), a minority of boys and men have significant problems with partial syndrome eating disorders or with the components of disordered eating such as binge eating, purging, or an obsession with being thin (see Croll, Neumark-Sztainer, Story, & Ireland, 2002; Muse, Stein, & Abbess, 2003).

As is the case for females, the risk of eating disorders and disordered eating is increased in subcultures where weight, size, and appearance are critical to success, and where the competitive edge is measured in small increments. Such contexts include wrestling, jockeys, light-weight rowing, and the gay community for males. Recently, researchers have turned their attention to boys and men whose dissatisfaction with being (actually with “feeling”) “too thin” and “too puny” drives them to become bulkier and more muscular.

If these goals are fueled by some of the common ingredients of eating disorders, notably anxiety, depression, self-consciousness about appearance, and fear of fat, the result may be a highly unstable body image, coupled with abuse of exercise, steroids, and food supplements (Pope, Phillips, & Olivardia, 2000). Clearly, there are groups of males, as well as females, who need selective and targeted prevention programs.

Second, men like me who want to contribute to prevention need to take seriously the stark implications of the following facts (for more details see Fallon, Katzman, & Wooley, 1994; Piran, 2001, 2002; Silverstein & Perlick, 1995; Smolak & Levine, 1996; Smolak &Murnen,2001, 2004;

Thompson et al., 1999):

• With regard to females, the high risk periods of early and late adolescence are development transitions that highlight the meanings of femininity in terms of body shape, sexuality, power, control, and achievement.

• Eating disorders and related problems for females (e.g., unhealthy dieting, abuse of stimulating, appetite-suppressing medication) have proliferated during historical periods like the present in which there is marked tension between expanding opportunities for females and continued reactionary emphasis on beauty, restraint, domesticity, and subservience to males.

• Risk factors for the continuum of disordered eating include sexual abuse, weight and shape related teasing or criticism, and the tendency to see females primarily in terms of the body as a sexual stimulus. In other words, patriarchy, including heterosexual objectification of girls and women, is an important factor in the widespread and often very serious phenomena of negative body image, helplessness, dissociation from internal signals of hunger and satiety, and other components of disordered eating.

These facts do not mean that females are inherently pure and supportive of each other, while arrogant and insensitive males are to blame for eating disorders. Such simplistic contentions are untrue and thus unhelpful.

As noted previously, no single group of people (e.g., advertisers, fashion designers, males, perfectionist parents) is solely to blame for complex cultural systems that support prejudice and encourage unhealthy behavior. But this diffusion of responsibility into the recesses of history and society (“that’s just the way it is”) does not mean that no one has a responsibility or a right to promote healthy changes.

It is indisputable that too many males, intentionally or automatically as a reflection of their upbringing, treat females in ways that set the stage for eating disorders and other psychological problems. As part of my commitment to prevention, I believe that everyone, males and females alike, shares the obligation to work with both males and females to improve health and well-being.

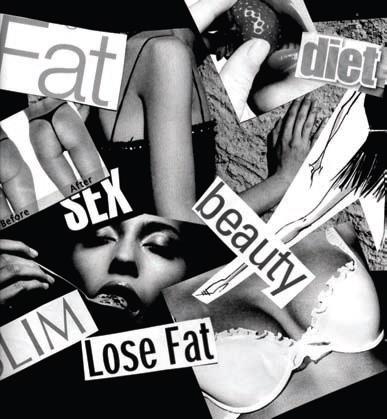

The third reason that eating disorders should be a very important issue for males follows from the second. Males are indeed a powerful, if not dominant, part of many of the cultural contexts that contribute to eating problems and eating disorders. For example, as businessmen and as consumers, males figure prominently in the construction, marketing, and use of mass media (including the multi billion dollar pornography industry) that glorify slenderness, vilify fat, and exploit the female body as a lifeless or endlessly compliant sexual commodity (Levine, 1994; Levine & Smolak, 1996; Thompson et al., 1999). Normative messages (e.g., “teenage boys are ‘just boys being boys’ when they leer at girls walking by in the hall or try to snap their bra straps,” or A fat women look silly and deserve ridicule for their lack of self-control) are accepted and amplified by many males, including grandfathers, fathers, and brothers operating within the tight emotional quarters of a family, as well as many other men who work with young boys and girls.

As family members, teachers, school administrators, physicians, clergy, coaches, Scout leaders—and, yes, as active members of organizations such as The Bronte Foundation—there is a great deal that males can do and be to make an individual and a collective contribution to minimizing risk factors for eating disorders and to increasing the resilience of girls and boys (Kelly, 2002; Levine, 1994; Maine, 2004).

It will not be easy, but one place for men to start is to acknowledge that individual boys and men— ourselves, our sons and brothers, our friends—need to be held accountable for their unhealthy attitudes and behaviors toward females.

3. Prevention of negative body image and disordered eating can be integrated with the prevention of obesity. Irrational beliefs and strong negative feelings about body fat and fat people (and fat women in particular), are key aspects of the cultural foundations of disordered eating in most countries such as the United States and Australia. So it stands to reason that prevention efforts should seek to reduce these irrational and demeaning attitudes.

But it also stands to reason that people engaged in health promotion should be very concerned about the high prevalence, the rising incidence, and the staggering multidimensional costs of obesity in children, adolescents, and adults. If we acknowledge the epidemic proportions of the obesity in many countries worldwide, then shouldn’t people be more focused on and more afraid of fat and have a higher, more determined and sustained investment in thinness?

And, if this is the case, then isn’t the prevention of eating disorders fundamentally at cross-purposes with the prevention of obesity?

These are critically important questions for people committed to prevention of eating disorders because many people (e.g., parents, teachers, pediatricians, government officials) in a position to promote health are much more concerned about the prevalence and health risks of obesity than they are about eating disorders.

This is a very complicated matter, especially since the well-funded, well-publicized, and intensive prevention campaigns (“wars”) against obesity in countries such as the United States have been spectacularly unsuccessful.

I have three recommendations for you to consider as you examine and (re)construct your own attitude about the matter with respect to the prevention of eating disorders. First, I strongly recommend

that you consult the well-researched and thought-provoking work of Frances Berg (2001, 2004) and Dianne Neumark-Sztainer (2003, 2005) in the United States and Rick Kausman (2004) in Australia. Second, based on this work, I encourage you to consider the possibility that the following mythology contributes to the proliferation of obesity, eating disorders, and the chaotic, undernourishing patterns of food consumption seen in many people of all ages:

• Being thin is healthy, good, and beautiful; being fat is unhealthy, bad, and ugly.

• Dieting, accompanied by a mentality emphasizing Asafe@ and Adangerous@ foods, is the only effective

way for people to manage their weight and to become slender or thinner.

• Fat people are obviously unhealthy, ugly, and responsible for their condition because they lack self control or have other psychological problems.

• At any size, your weight is a very important and very clear marker of your health status, and even

small increments in weight are dangerous.

Finally, isn’t it time for a new paradigm, one that emphasizes “health at every size” (Robison, 2003; see also BodyPositive.com)? Even though it is highly debatable whether there are no sizes that are unhealthy in and of themselves, the key concept here is “health,” not a certain size or weight or shape. Health is define as the strength, stamina, and energy to carry out your responsibilities and to pursue your interests, the resources to resist illness, the emotional well-being to participate fully in life, and the inclination and the ability to develop positive social relationships.

Defining our goals in terms of health promotion is a fruitful starting place for integrating the prevention of eating disorders with the prevention of obesity. Here is a list of goals that could be fertile common ground for prevention efforts by families, individuals, individuals, professionals, and organizations (see Neumark-Sztainer, 2005):

• Everyone is entitled to a positive body image that is supported by respect and appreciation for the diversity of human sizes and shape.

• Everyone would benefit from an active lifestyle characterized by play, physical activity instead of mechanical motion whenever possible (e.g., walking or biking instead of driving or using the elevator), and less time spent in front of the television. An active lifestyle should as much as possible, incorporate regular, moderate exercise that is done for fun, fitness, and friendship, not to compensate for having eaten “forbidden foods.”

• Everyone can improve his or her eating habits, for example, by increased consumption of complex carbohydrates such as fruits, vegetables, and grains, and decreased consumption (but not elimination) of red meat, saturated fats, salt, sugar, and soft drinks.

. Everyone can learn to eat in ways that satisfy hunger; provide energy for health, growth, and well-being; and are regulated–not by calorie-restrictive dieting and other externally imposed rules–but by being attuned to feeling hungry and to feeling full.

• Everyone can find more opportunities for communal eating, that is, ways to ensure that family and friends sit down and enjoy food together in a friendly, nurturing atmosphere.

• Everyone can refrain from or reduce the use of soft drinks, cigarettes, and other drugs designed to suppress appetite.

• Everyone can learn—and help others to learn–life skills to cope with stress and to meet her or his needs in ways that do not include starving and/or anesthetizing feelings by binge eating.

Note that this perspective I am asking you to consider does not ignore the needs of fat children or other people struggling with a weight that is too high or too low. Nor does it replace an unhealthy dichotomy of “safe vs. dangerous foods” with the equally dysfunctional contrast of “dieting is always bad vs. eating whatever your body craves is fine.”

The point is that an attitudinal shift from body weight, dieting, and external regulation to health and health promotion will likely serve us well in preventing eating disorders and obesity. Moreover, construing health in bio-psycho-social terms is quite consistent with the aforementioned lesson learned many people suffering from eating disorders and by their families: At one important level, eating disorders reflect much more than problems with weight, shape, eating, and weight management.

4. Prevention requires a critical/analytic perspective, attention to social justice, and activism–and thus it requires dialogue, collaboration, and courage. The individual psychopathology of anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa has its foundation in a number of unhealthy cultural beliefs, attitudes, and behaviors, some of which certainly deserve to be called “prejudice” and attacked as such (Bordo, 1993; Gordon, 2000; Puhl & Brownell, 2001, Smolak & Murnen, 2001, 2004). “Prejudice” and “discrimination” are ugly words that represent ugly, poisonous, and destructive practices. Consequently, they are not to be used lightly.

So ask yourself, your family, and your friends: Why do so many more females than males suffer from eating disorders and disordered eating? Why are eating disorders and obesity so prevalent in our modern, fast-paced, global, and shifting societies? Why are weight and shape so important? What motivates an uncontrollable fear of fat and an oppressive, obsessive investment in being thin or becoming muscular?

Why would one see oneself as “nothing” and “a worthless failure” if one gained 5 pounds? What underlies the extremes of control and lack of control, of restraint and indulgence?

I implore you to consider carefully and at length the answers to these questions. To resist negative cultural influences (e.g., the lure of advertising, the promise of dieting) and to develop ourselves and our institutions as sources of resilience and health, we need to think critically about the positive, negative, and ambiguous forces influencing our lives and the lives of those at greatest risk for disordered

eating (see, e.g., Fallon et al., 1994; Kilbourne, 1999; Maine, 2000, 2004; Piran, 2001; Smolak & Murnen, 2004). “Critical” thinking is not an invitation to pessimism and cynicism. Its ultimate purpose is constructive, and it builds on an appreciation and celebration of positive factors.

I implore you to consider carefully and at length the answers to these questions. To resist negative cultural influences (e.g., the lure of advertising, the promise of dieting) and to develop ourselves and our institutions as sources of resilience and health, we need to think critically about the positive, negative, and ambiguous forces influencing our lives and the lives of those at greatest risk for disordered

eating (see, e.g., Fallon et al., 1994; Kilbourne, 1999; Maine, 2000, 2004; Piran, 2001; Smolak & Murnen, 2004). “Critical” thinking is not an invitation to pessimism and cynicism. Its ultimate purpose is constructive, and it builds on an appreciation and celebration of positive factors.

Developing an “attitude” that embodies a critical perspective is a challenging process, one that requires opportunities to think, read, investigate, discuss, and reflect. Thinking critically also requires courage and various forms of support, particularly in cultures that emphasize individual achievement, aggressive competition, and conspicuous consumption.

At least some evidence from the field of prevention itself (see Piran, Levine, & Steiner-Adair, 1999) indicates that a critical perspective, or “consciousness-raising” if you will, is best fostered in the context of supportive relationships, the opportunity for dialogue, and a mentor-model who is not afraid to think critically, to galvanize others to do the same, and to take action based on the knowledge developed through reflection and appraisal. If you are wondering where one might find such “models,” I recommend you spend 30 minutes or so with Jan Cullis of the Bronte Foundation, and that you attend presentations by or read the work of Niva Piran (2001, 2002), Margo Maine (2000, 2004), Joe Kelly (2002; see also Dadsanddaughters.com and Maine & Kelly, 2005), and Sandra Friedman (2000, 2003).

Let’s return for a moment to the questions posed at the beginning of this section. For example: What motivates an uncontrollable fear of fat and an oppressive, obsessive investment in being thin or becoming muscular? And why would one see oneself as “nothing” and “a worthless failure” if one gained 5 pounds?

Research and clinical practice have shown that it is useful to think of the beliefs and feelings represented in these questions as “symptoms” or “schematic distortions” to be eliminated by therapies for eating disorders such as CBT. However, as I’ve emphasized time and again in this essay, this psychiatric approach to individual suffering should not obscure the fact that these attitudes (e.g., overvaluation of weight and shape, glorification of the tall, slender, mid-pubescent look, the fear of fat, and the vilification of fat people) and practices (e.g., self-starvation, excessive exercising, binge-eating) are rooted in widespread prejudice against women, fat people, aging, and ethnic minorities (Bordo, 1993; Fallon et al., 1994; Piran, 2001; Smolak & Murnen, 2001, 2004).

This means that our critical consciousness, our dialogues, and our constructive actions must address, not just the dangers of dieting, but emotionally and politically charged topics such as fear of women’s desires and hungers; sexual harassment and sexual abuse; limitations in women’s avenues for success apart from beauty and sexual objectification; oppression of minorities; and the role of big businesses that profit from female and male anxieties about gender roles, weight, and shape.

Raising our own awareness and creating opportunities for ourselves to experience and articulate strong feelings about what is unjust and unhealthy lead to a strong desire to take constructive action. It is a logical and inevitable step to move from “something’s very wrong here” to “what exactly is going on?” to “I/We know what’s going on here and it makes me/us feel outraged” to “somebody ought to do something to correct this” (Piran, 2001; Piran et al., 1999).

In more formal terms, this critical social perspective (Levine & Piran, 2004; Piran, 2001) emphasizes an ongoing cycle of the 5 A’s (Levine, Piran, & Stoddard, 1999): Awareness, Analysis, Activism & Advocacy, and Access to power and other mechanisms of change. I see The Bronte Foundation, using its own conceptual models and hard-earned wisdom, as passionately engaged in this cycle.

I hope this article will prompt you to analyze aspects of your own attitudes and those of the culture(s) in which you live. This is a crucial step in developing a sense of what actions you might take as an advocate for prevention and health promotion. In the next installment, I will present an overview of some specific things that you and I can do and be in our everyday lives to help prevent negative body image, disordered eating, and eating disorders.

References included in PDF version of this article.